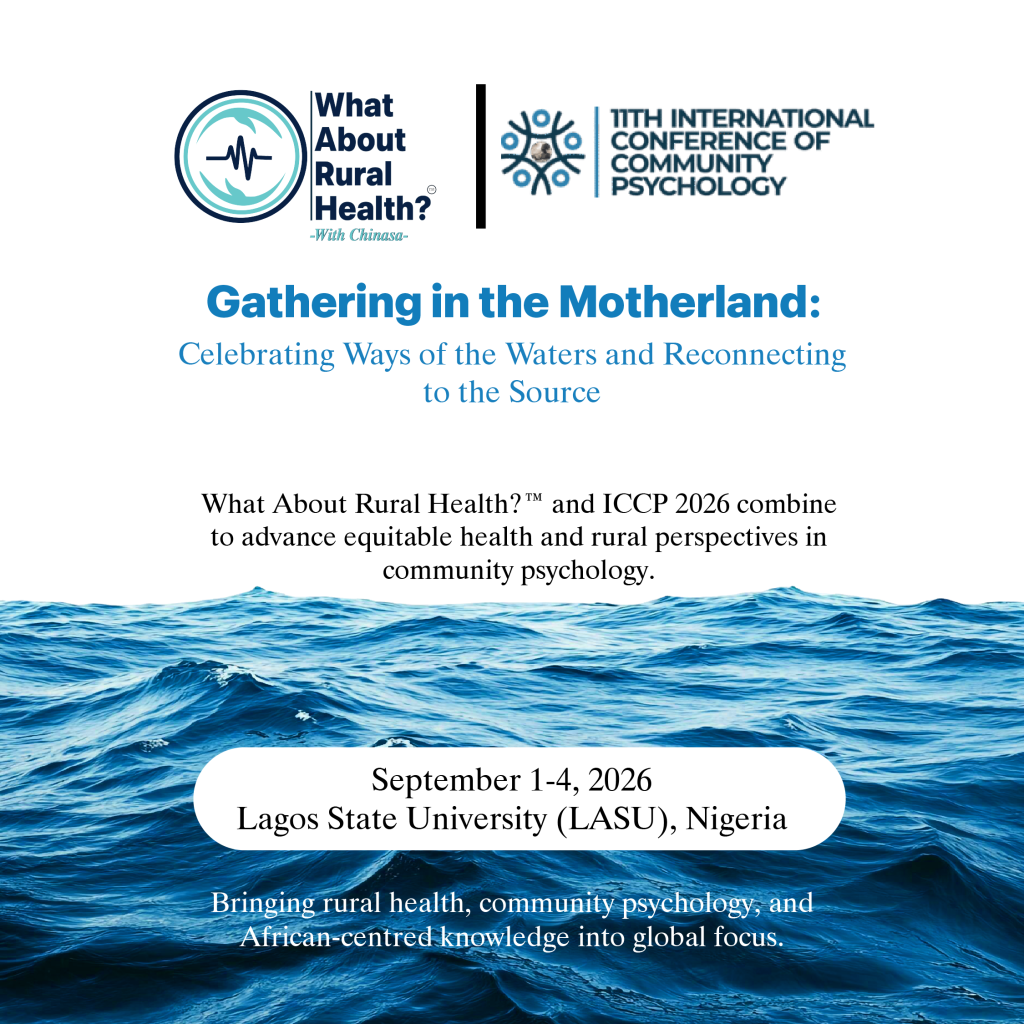

What About Rural Health?™ Partners with ICCP 2026 Conference in Nigeria

ICCP 2026 partners with What About Rural Health?™ to translate community psychology into action for rural and underserved communities.

10 Takeaways from the 2025 World Health Summit: Why Africa Must Pay Attention

Discover key insights from the 2025 World Health Summit and why Africa must pay attention to global health priorities shaping the future of healthcare.

Between Hills and Hope: Rethinking Rural Sexual and Reproductive Health in Rwanda

Explore sexual and reproductive health in Rwanda—real stories of resilience, teenage pregnancy, and hope rising across rural communities.

So What About Healthcare Funding For Rural Nigeria?

Discover the state of healthcare funding in Nigeria, challenges facing rural health, and sustainable financing solutions for equitable care access.

Explained: The UNGA’s 2025 Bold Resolve on NCDs and Mental Health

The UN General Assembly’s new political declaration on NCDs and mental health urges global action—but will rural communities be left behind?

2025: Deadliest Ebola Strain Strikes DR Congo Again

2025: Ebola strikes DR Congo again. Kasai faces Zaire Ebola virus with 81 cases, 28 deaths, and urgent vaccination efforts underway.

The Negative Truth About Cholera in Africa

Explore the hidden truth about cholera in Africa—recent outbreaks, death tolls, and why strengthening rural health systems is critical to stopping the disease.

What About Rural Health? Convener Bags WHO Civil Society Appointment

‘What About Rural Health?’ Convener Appointed to WHO Civil Society Commission Steering Committee

When There Is No Pharmacist

Without a pharmacist, rural communities face deadly risks from unsafe drug use. Discover why pharmacists are vital for safe, effective care.

SO WHAT ABOUT RURAL HEALTH?

Explore rural health challenges and solutions—from access gaps to telemedicine—and why investing in rural care benefits us all.