A Women’s Reaction to the Real Global Fertility Rate Crisis

By Chinasa Imo | What About Rural Health?

Global Fertility Rate Is Falling — But That’s Not the Whole Story

The global fertility rate is on the decline. According to the UNFPA’s 2025 State of World Population Report, the global average now sits at 2.2 births per woman—down from 5 in the 1960s. By 2050, it’s expected to fall below the replacement level of 2.1.

But here’s the critical point: the crisis isn’t that people are choosing smaller families. It’s that millions are unable to have the number of children they want—because of poverty, healthcare gaps, and systemic inequality.

The Real Crisis? Reproductive Agency

UNFPA surveyed 14,000 people across 14 countries and found that:

“1 in 4 people haven’t had or expect they won’t have their desired number of children.”

It’s not biology that’s the problem—it’s barriers.

257 million women worldwide want to avoid pregnancy but lack access to modern contraception (UNFPA, 2025).

This isn’t a personal shortcoming — it’s a systemic failure.

That’s where the popular “fertility crisis” narrative falls apart. It assumes people are making free, empowered choices — but for many, that freedom doesn’t exist.

Take Namrata, a working mother in Mumbai, whose story was featured by the BBC. She and her husband hoped for a second child, but the high costs of raising just one — from healthcare to school fees — made that feel out of reach.

Her experience mirrors findings from the UNFPA survey, where the most common reasons for not having more children were: lack of money, lack of time, and lack of support.

When policymakers say, “people are choosing to have fewer children,” we need to pause and ask: is it truly a choice?

Because the data tells a different story:

-

Many are having fewer children than they would like — not out of preference, but due to financial strain and structural barriers.

-

Others are having more than they intended — because they lack access to contraception and control over their reproductive lives.

In both cases, the common thread is a loss of agency. It’s not just about birth rates — it’s about whether people can actually decide for themselves.

In Rural Communities, Fertility Rate has a Grim Face

In remote areas of countries like Nigeria, India, and South Africa, women face compounding obstacles:

- Long distances to clinics

- High maternal and infant mortality rates

- Limited contraceptive options

- Child marriage and low educational opportunities

And while urban discussions focus on fertility incentives and work-life balance, rural women are still fighting for access to basic healthcare.

You can’t make empowered choices when you’re facing gender-based violence, malnutrition, forced marriage, and poverty every day. In such conditions, “choice” is an illusion.

While sub-Saharan Africa hasn’t reached below-replacement fertility, early shifts are emerging due to urbanization, increased education, family planning access, and gender equality efforts—contributing to a gradual, organic decline.

The takeaway? Behind every data point is a real story. And behind every fertility decline is a system.

Instead of asking how many children women are having, we should be asking: why are they having fewer—or none at all?

Stop Treating Women as Birthrate Solutions

Countries like Hungary, South Korea, and China are now offering cash incentives and launching pro-natalist campaigns to boost birth rates. But this approach misses the mark.

Rather than creating inclusive systems that respond to what women actually need, these governments are pressuring women into motherhood (Lee, 2025; Friedman, 2024; Kwon, 2024; Tan, 2023).

Policies rooted in panic will always fall short.

True reproductive justice means building systems of care that support informed, empowered choices—whether that’s having children, not having them, or choosing to wait.

Fertility support should begin with rights, not rewards.

More: Why Hungary’s Subsidies Failed

Saying “No” Can Be a Powerful Act

One of the most powerful insights from the UNFPA report is this: many women aren’t avoiding children because they don’t want them—it’s because the system makes it too risky.

For some, choosing to stop at one or none isn’t apathy—it’s survival.

As a woman in the Philippines put it:

“A lot of policies are against women’s healthcare. It pushes us to stay single and have no children.” (UNFPA, 2025, p. 9)

When systems fail—through violence, poverty, or inadequate care—women don’t give up. They opt out to protect themselves.

This policy feedback loop is not apathy; it’s risk management.

Reframe the Narrative: Fertility Should be About Choice

Rather than crafting policies to manipulate fertility rates, we need to shift the focus to what truly matters: supporting women to thrive.

When women—especially in rural communities—feel safe, heard, and supported, they make choices that benefit their families and society.

The real issue isn’t low birth rates. It’s that too many women still lack the agency to make life-defining decisions about their bodies and futures.

What’s needed are policies that trust women, invest in health systems, and create conditions where reproductive autonomy is not the exception—but the norm.

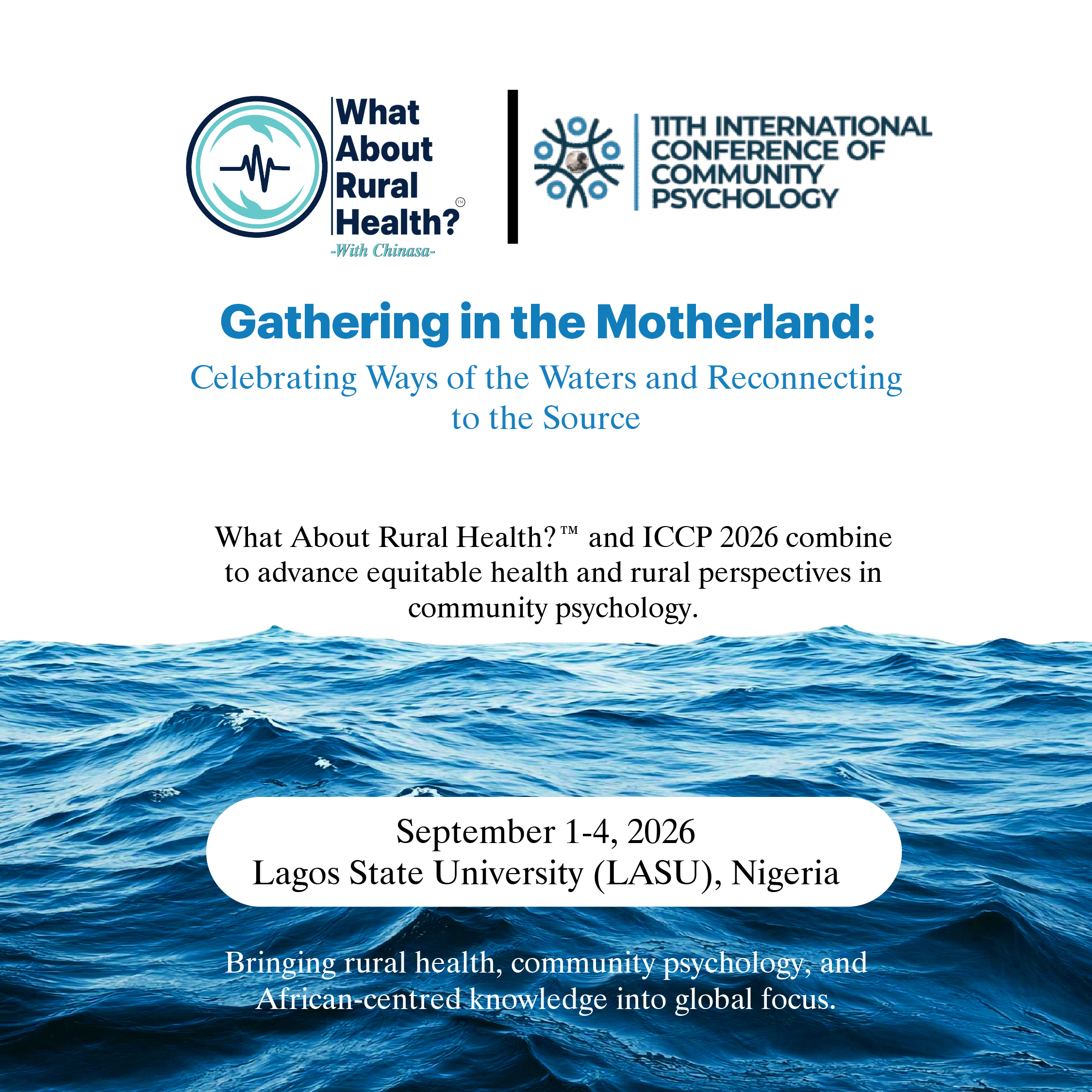

At WhatAboutRuralHealth?™, we believe the solution isn’t more babies. It’s more support, options, and freedom.

Rural women must be at the center of reproductive health conversations—not as passive recipients or population targets, but as leaders. They deserve dignity, care, and platforms to be heard.

That means:

-

More investment in rural health systems

-

More protection from gender-based violence

-

More clinics

-

More spaces—like this one—for rural women to speak their truth

Because the real fertility crisis isn’t about numbers. It’s about equity.

True progress is when every woman can say:

“Yes, I want a child.”

“No, not right now.”

“This is enough for me.”

What You Can Do

Reproductive justice = reproductive choice.

If you’re a health worker, policy expert, or rural community member, we want your voice in this conversation.

Submit your rural health story here

Join our volunteer collective

References